The Gift of Humility

It’s been a busy few weeks. Two Sundays ago, we spoke at West Shore Unitarian Universalist. From the pulpit, Emily was able to thank Mary Jo, a woman in the congregation who had “dropped out of the sky,” and helped her so much in the beginning days of coming to terms with my dementia diagnosis.

Next, we traveled to Washington, D.C. where I participated in a panel discussion for the Us Against Alzheimer’s Summit. Taking my place as a dementia advocate with my friend and award-winning journalist Greg O’Brien who has Alzheimers, I was able to thank Greg who has taught me much about living with early onset dementia.

This past weekend, Emily and I traveled to Westford, Massachusetts, where at the invitation of Wellfleet friends and summer parishioners, Herb and Elizabeth Elliott, we spoke at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. It was a beautiful fall weekend, complete with New England color and seafood, as well as connecting with old friends and colleagues.

At our Saturday afternoon session, two women who had driven from northern Vermont to hear us, said that we had become their lifeline as they were dealing with a new diagnosis of FTD-PPA. They had seen us on Sixty Minutes; they had followed our blog, and they had read about us in the newspaper. Wow! We were blown away with honor and humility to realize that, like Mary Jo and Greg, we were helping somebody else along the path that we are traveling. It’s a very small world.

Jesus says: “All who exalt themselves will be humbled but all who humble themselves will be exalted.” (Luke 18.14) Want to learn about humility? Get a dementia diagnosis. That’s what happened to me three years ago when I was diagnosed with Frontotemporal Degeneration, a rare form of early onset dementia.

FTD has allowed me to learn about humility the hard way. For most of my adult life, I wore a uniform identifying my profession, had the best seat in church, held a place of honor at banquets, was greeted with respect in the marketplace, and people called me “Rev.” or “Dean.”

Then one day, it was over. The doctor told me that if my condition followed its usual course, in a matter of years, I would be unable to read, write, or understand language; then I wouldn’t be able to swallow; then I would die. He suggested that we should get our affairs in order, and I should make the most of my remaining time.

Within three months of my diagnosis, my career was history. The newspaper articles announcing my retirement were in the archives. I had bid farewell to my congregation and staff. My books and vestments were packed. I was without a title, office and church keys. My calendar was empty, except for a disconcerting number of medical appointments, and my email inbox was reduced to advertisements and listserve messages.

When that first Sunday of “retirement” rolled around, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I woke up late, read the paper, and drank a third cup of coffee. I thought about going to a local church, but instead, I sat in bed and wrote a poem, in which I described myself as “a little boat untethered on a big lake [with] wind and waves pushing away from familiar shore.” Like many newly retired and unemployed people, I didn’t know who I was without my title and position.

It’s hard losing your status and place in society; those of you who have lost jobs and/or spouses understand. It’s hard losing the identity you’ve taken for granted; certainly, immigrants and refugees in this country know what I’m talking about. And, it’s hard—really hard—losing your strengths; those of you who are struggling with health issues know of what I speak. To say, it’s humbling is an understatement.

I don’t think that humility was ever one of my strong suits. In fact, if I’m being honest, pre-FTD, I think I could have been characterized as being self-assured, and at times, a bit arrogant. But, when I started showing signs of cognitive impairment, my self-assuredness and arrogance quickly evaporated.

When you don’t know what day of the week it is; when you can’t remember whether you brushed your teeth, showered, or took your medicine; when you get disoriented in a crowd or startled on a busy sidewalk; when you stutter or shout, and use incorrect words or incomplete sentences in an effort to make yourself understood; when you become immobilized by choices and decisions; when you forget how to do a simple task; when you cross the street without regard to traffic; when you have a tantrum in public, burst into tears for no good reason, or even help yourself to food off of a stranger’s plate — pride goes out the window.

It is humbling to live with dementia. However, Jesus, who “humbled himself on a cross,” says that humility is a good thing. In fact, in the Gospel of Matthew, when instructing his disciples to take up his yoke and learn from him, Jesus refers to himself as “humble of heart.” (Mt 11.20)

Humility is considered a virtue, something to work towards or strive for. The Hebrew prophet Micah says, humility, accompanied by justice and kindness, is what God expects of us. (Micah 6.8) Benedict, the 5th-century founder of western monasticism, understood humility as the path, or “the ladder,” by which we ascend to “that perfect love of God which casts out fear.”

The Quran considers humility to be the highest knowledge. Thus it is written: “The servants of the Most Merciful are those who walk upon the earth in humility, and when the ignorant address them, they say words of peace.” (Surah Al-Furqan 25:63)

The I-Ching, the ancient Chinese guide for living an ethical life, explains the benefits of humility this way:

Yield and overcome;

Bend and be straight;

Empty and be full;

Wear out and be new;

Have little and gain;

Have much and be confused;

Therefore wise [individuals] embrace the one

And set an example to all.

Not putting on a display.

They shine forth

Not justifying themselves,

They are distinguished.

Not boasting,

They receive recognition.

Not bragging,

They never falter.

They do not quarrel,

So no one quarrels with them.

Therefore the ancients say,

“Yield and overcome.”

Be really whole,

And all things will come to you.

According to the perennial wisdom that crosses all religious boundaries, humility is a way of becoming whole and fully human. So what exactly is humility?

Day by day, I’m learning that humility is about both acknowledging and accepting what I can and cannot do. I’m learning this is truth in the adjustments and adaptations that I’m making to live with dementia. It’s hard, but it’s essential for my well-being and those around me. I’m also learning that as my strengths don’t make me more of a child of God, my limitations don’t make me any less of a child of God. In fact, coming to terms with both my abilities and my disabilities is helping me to find and claim my rightful place in relation to God and neighbor. It’s giving me new eyes to see Christ in the other. And, it’s changing my attitude about acceptance of myself and of others.

My colleague and friend Robert Morris once wrote that “true humility … is the fruit of a keen-eyed ability to see oneself realistically, as a flawed and gifted creature like all other human beings.” Quoting St. Paul, he reminds us that, “You should not think of yourselves more highly [or more lowly] than you ought to think.” (Rom 12.3) Morris continues: “When we humbly accept our own reality as it comes, we are better able to see the world as it actually happens around us. We then can see more clearly what’s called for the here and now regardless of what’s in it for us.”

So how do we cultivate humility? Well, I don’t think you have to get dementia. However, you do need to make an honest self-assessment of yourself. As the Pharisee learned in this morning’s gospel story, it’s not about justifying yourself in order to feel superior to someone else. Rather, it’s about accepting the good, the bad and the ugly, and realizing that it all comes from the dust, and to dust, it all (and we all) shall one day return.

In yoga, there is a position called “Child’s Pose.” It’s considered an “active” resting pose with knees bent, forehead on the ground, and arms stretched out in front. Whenever I find myself in Child’s Pose, I think of is as prostration, an ancient prayer posture. For me, “Child’s Pose” becomes a moment of prayer, a time of re-centering and reminding myself that the universe is a big place, and I’m one small participant in its grand story. Any way you look at it, getting down on your knees or flat on your stomach, placing your hands in front of your body on the ground, and lowering your head till your forehead touches the ground is a humbling action.

Almost without exception, when I’m in Child’s Pose, I also am reminded of just how hard it is for me to be humble. I identify with the 11th-century French abbot Bernard of Clairvaux who once said that rather than ascending the Benedictine ladder of humility with grace, he was better prepared to slide down it.

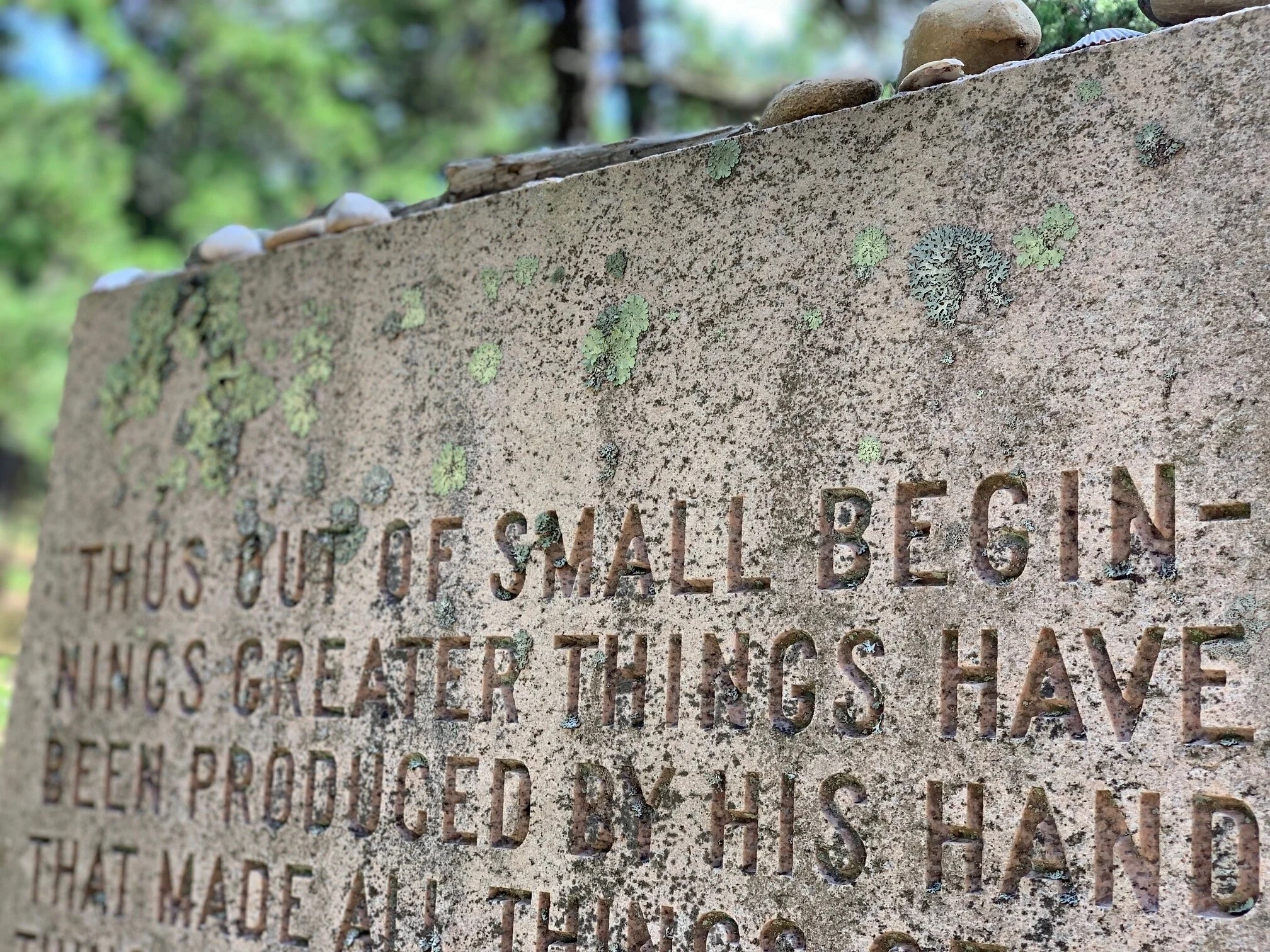

So true, so true. If we’re honest with ourselves, most of us fall or trip into our humility. I know that I have, and I bet you have or will have as well. The virtue of humility is a complicated thing. We all would be wise to give it consideration before it demands our attention. But when it does, and it will, if we accept it, this curse will become a gift and will lead us into the fullness of life.

Referenced Material: Benedict of Nursia, Rule for Monasteries 7:67, The Rule of St. Benedict, ed. Timothy Fry (Collegeville, Minnesota: the Liturgical Press, 1981), Tao Te Ching: A New Translation, Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English (New York: Vintage Books, 1972), Henri Nouwen, Bread for the Journey (1997), Robert Corrin Morris, “Meek as Moses: Humility, Self-Esteem and the Service of God,” Weavings, Volume XV, Number 3 (May-June 2000), M. Basil Pennington, “Bernard’s Challenge,” Weavings, Volume XV, Number 3 (May-June 2000)