Dementia: A spiritual lesson in forgiveness

When the wrong word comes out of my mouth, when I do something inappropriate in public, when I don’t recognize a face or can’t recall the name of a close friend or relative; when I get flustered, confused, agitated or angry at someone for no good reason; when I can’t follow through on a simple project or activity, when I forget to show up for an appointment or lunch date; or when I attempt to cross the street unaware of oncoming traffic, I have to ask for the forgiveness of others.

When well-intended people say inappropriate and hurtful things about my condition, or about dementia in general, or when because I’m doing well, they question the diagnosis, I have to forgive them.

I’m also working hard to forgive myself for the ways I took brain health for granted and neglected my own self-care as I cared for others. What if I had exercised or meditated every day; what if I had managed stress more effectively; what if I hadn’t worked such long hours or gotten more sleep. The list of “what if’s” goes on and on. Since I can’t turn back the clock, I need to forgive myself, even as I try to live a healthier lifestyle.

Coming to accept the new me and learning to live in the here-and-now, I also realize how important it is to forgive the hurts, betrayals and injustices of the past. My shrinking brain simply doesn’t have room for all that stuff. Carrying grudges and guilt can become a very heavy burden. Jealousy, resentment, envy, rage, and despondency are really toxic for our brains, our spirits, and yes, our souls. So as I cleanse myself from environmental toxins, I’m also trying to get rid of spiritual toxic waste. This requires me to forgive those who knowingly or unknowingly have done me harm, and to seek forgiveness for the harm I’ve done to others.

More and more, I’m discovering that forgiveness is pretty good spiritual and cognitive medicine. I’m also coming to understand that forgiveness actually makes room in our hearts and minds for joy, love, healing and new life. In fact, I think it is one of the key ingredients in the recipe for cultivating the fullness of life.

While forgiveness appears to be a simple matter of letting go and letting God, it’s not that easy. Or, as C.S. Lewis observed in Mere Christianity, “Everyone says forgiveness is a lovely idea until they have something to forgive.” I can think of no truer saying.

Forgiveness actually leaves me with lots of questions. How does one forgive the spouse who betrayed your trust, the employer who made unreasonable demands, the parent who was overly critical or unattentive, or the friend who neglected your friendship? And those are just the ordinary hurts of being human. What about the big stuff, like the Holocaust, slavery, apartheid, sex abuse scandals, political corruption, corporate greed, and environmental genocide? How do we forgive institutional betrayal, social damage, global abuse, and collective sin? Are there limits to forgiveness; if so, what are they?

To forgive, in Greek, means “to let go, or set free.” From the cross, Jesus prayed: “Abba-Father, forgive them,” (Luke 23.34) and then he let go and returned to God. By the way, biblical scholars dispute whether “for they don’t understand what they do” is a later addition to the text.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus taught his followers about forgiveness. In fact, when they asked him how to pray, Jesus taught these words: “Forgive us our sins and trespasses as we forgive those who sin and trespass against us.” (Luke 11.14, Matthew 6.12) He also insisted that what we release on earth will be released in heaven, and what we bind on earth will be bound in heaven.

When we forgive or ask God to forgive, we are seeking to let go of the burdensome hurt that we’re carrying, to release the burden of another, and thus re-establish a broken relationship. In essence, through forgiveness, we seek to move to a new place of freedom and liberation, of rest and peace, of healing and wholeness.

It’s hard to forgive, especially when we’ve been really hurt, insulted or demoralized. That’s why Jesus said that in order for us to feel fully human, we have to be able to forgive others, even — perhaps especially — those who hurt or offended us the most. Jesus insisted that there is no one undeserving of forgiveness, even if we can’t offer it.

I’ll never forget sitting with a therapist as I struggled to forgive someone who had really hurt me and my church. I kept insisting that I needed to forgive this person, but I simply couldn’t do it.

After listening to me talk about it for a few weeks, the therapist asked, “Why do you need to forgive him?” I was taken aback. Nobody had ever posed that question before. Stammering for words, I replied, “Because Jesus tells me so.” But I couldn’t do it. I was stuck.

For years, I kept trying to forgive this person, but with no success. The more I tried, the more angry, frustrated and hurt I became. It was as if I was carrying this guy around in my arms, like a dog that has stolen a glove and can’t put it down to fetch a steak bone.

Eventually, I sought counsel from another priest. After telling her my story and my stuckness, she said, “I’d like you to make a confession.” “Why?” I asked. “Because, you are not able to forgive yourself for allowing him to hurt you, and for not being able to forgive him.”

Now, that’s ridiculous, I thought. But I agreed to give it a try. So I got down on my knees and made my confession, asking for God’s forgiveness of me, the one who felt like the victim.

In keeping with the sacrament of reconciliation, my confessor offered “words of comfort and counsel.” She instructed me to pray for this person’s well being every day until I was no longer angry. I responded, “That will be very difficult, but I’ll try.” She said, “Don’t try; just do it.”

I began to pray every day for the one who had wronged me, and slowly but surely, my anger started to soften and my hurt began to dissipate. I also started to see that person in a new light, actually feeling some compassion and pity for him. But it took months — no, years — of prayer.

“How many times am I to forgive another...” asked Peter. “As many as seven times?” “No,” said, Jesus, “Not seven times, but, I tell you, seventy-seven times” or depending on how you read the text, perhaps “seventy times seven.” (Matthew 18.21-22) Jesus understood how hard it is to forgive. That’s why he said it might take a while.

All of us have broken relationships, moments and places in our lives that require forgiveness. As we approach the holiday season, I would invite you to take the time to ask yourself: "Who in my life needs forgiveness?" And, I would encourage you to make that work part of your holiday preparation, maybe even consider it could an early present to yourself and someone in your life.

On November 14, 1940, the city of Coventry, England was bombed. The Cathedral was destroyed. The morning after, Provost Richard Howard declared that the Cathedral would be rebuilt as a symbol of faith and hope for the future. He also declared that the Cathedral would pray for their enemies. This decision led to Coventry Cathedral’s worldwide ministry of reconciliation.

In the midst of the rubble, the cathedral’s stonemason found that two charred medieval roof timbers had fallen in the form of a cross. He set them up in the ruins. They were then placed on an altar of rubble with the words “Father Forgive.” Other crosses have been made from the cathedral’s medieval nails and have been given to cathedrals around the world engaged in the work of reconciliation. Trinity Cathedral, Cleveland is a bearer of one of these crosses.

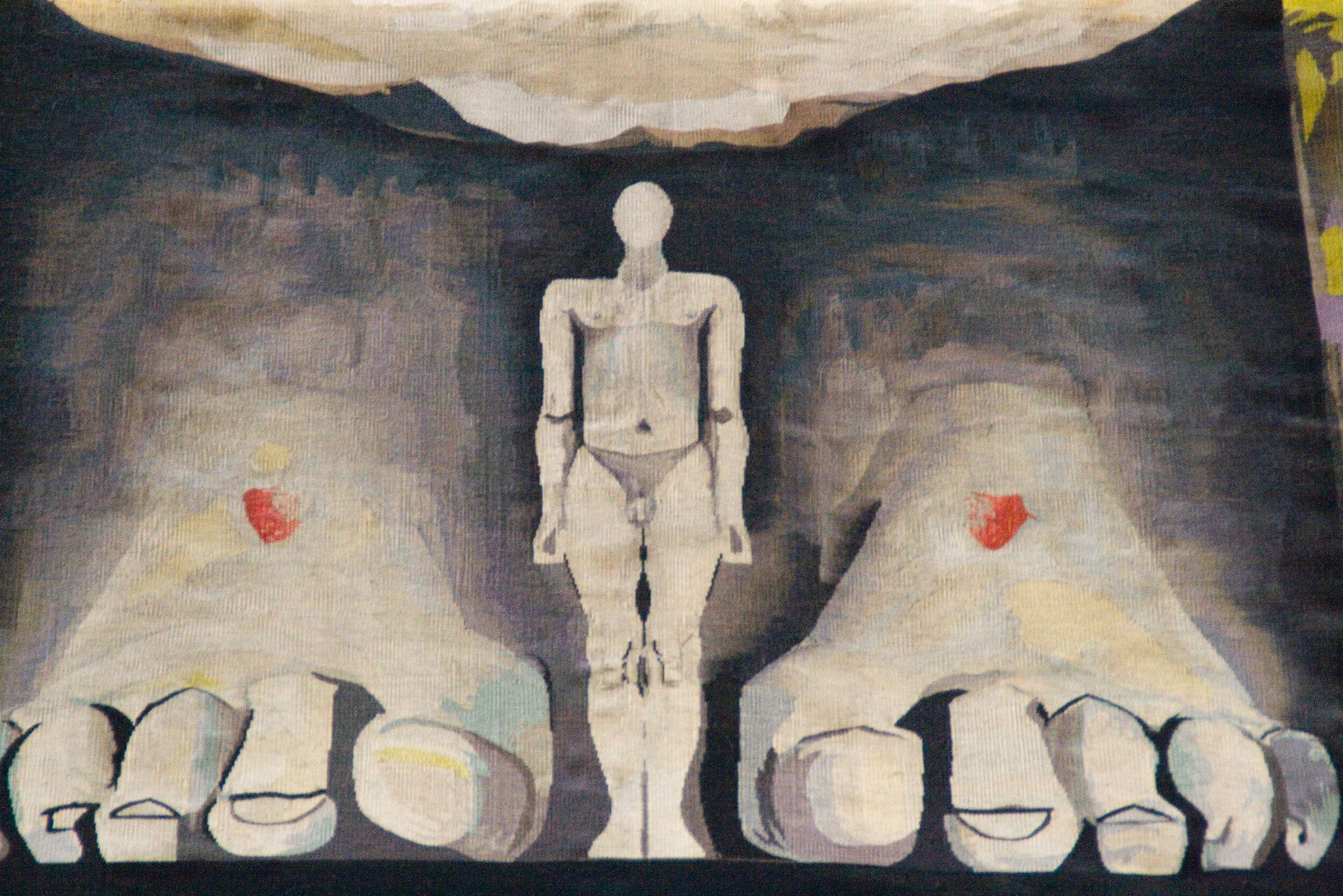

Emily and I visited Coventry Cathedral in 2007. These are photos from that visit. They remind me of the ongoing, difficult work of forgiveness and reconciliation.