The Courage to Hope

“Of St. Paul’s trio of Christian virtues — faith, hope and love — the greatest of these is love, but the most neglected virtue is hope.” - Former Archbishop of Canterbury Donald Coggan.

Hope has become a precious and diminishing commodity. Many of us are not hopeful about the direction of U.S. foreign and domestic policy. Many are not hopeful about the future of our environment. Many are not hopeful about their own finances, housing, health, or even food security.

Why? We’re certainly not the first generation to face serious challenges. Our ancestors lived in troubling times. What’s different? Why are suicide rates climbing and birth rates declining? Why are dystopian novels, films, and television shows so popular? Why are so many among us cynical and disengaged? What threatens and even destroys people’s sense of hope?

I think it’s fear. Fear is the greatest threat to hope. Some of us fear that our political and economic system is out of control. We fear that we, or our children and grandchildren, along with other species, are compromised and will eventually be annihilated by the technology and climate we’ve created.

Some people fear that there will be no place for them in our land. Others fear that strangers will take over our land. The millennial generation fears their downwardly mobile trajectory. Lots of us fear growing old without adequate resources and support systems. The most desperate and hopeless among us fear that life itself has become meaningless.

Hopelessness, the outgrowth of fear, is the energy drain of humanity.

Why bother? Life stinks, and then you die.

I believe that hopelessness is a conspiracy of evil that keeps us in bondage. Without hope, people give up and die. Dostoevsky puts it this way: “To live without hope is to cease to live.” I am convinced that the evil powers and principalities of this world conspire to make and keep us hopeless and therefore imprisoned in our perceived powerlessness.

Yet hope is at the very essence of faith. In Hebrew, “hope” means “to wait for” or “look to.” Thus, the author of Hebrews writes: “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” (Hebrews 11.1)

When I received my diagnosis of Frontotemporal Dementia, I was anything but hopeful. But eventually, I got my act together and decided that I am going to live as fully as I can for as long as I am able.

For the past two years, as Emily and I travel speaking and preaching about life with dementia, it often seemed as if we had opened Pandora’s Box, talking about a condition that many fear and dread. One day, Emily asked me if I actually remembered the ancient Greek myth of Pandora’s Box and suggested that I re-read it. Let me remind you of the story.

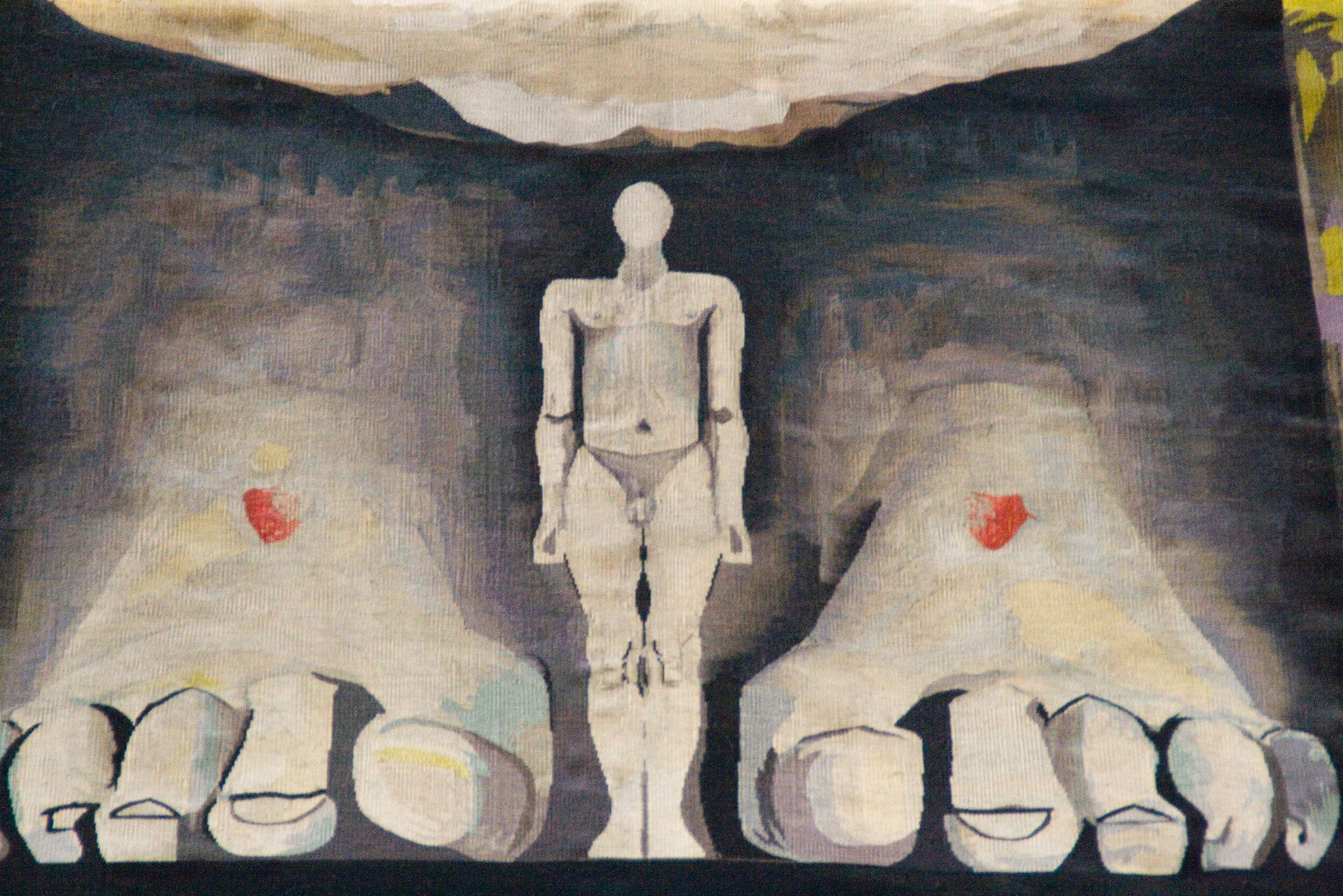

Once upon a time, there were two brother gods whose names I can no longer pronounce. One day, one of the brothers discovered the secret of fire, and this angered Zeus. As punishment, Zeus chained him to a rock for many years. And if that wasn’t enough, the great god went after his brother by way of trickery. First, Zeus ordered the god maker of all things to craft him a daughter out of clay. Zeus named her Pandora, brought her to life, and gave her as a bride to the brother. Zeus then gave the newlywed couple a gift – a locked box with a note that said, “Do not open.” Attached to the note was a key.

Of course, you know what happened next. Pandora’s curiosity got the better of her, and she took the key and opened the box. When she raised the lid, lots of bad things – envy, sickness, hatred, disease, war, pestilence, and famine – flew out into the world. By the time Pandora closed the lid, it was too late. The world was no longer perfect.

That’s how most of us recall the myth. But there’s more.

Pandora’s husband heard his wife crying and came running. She opened the lid to show him that the box was empty. When she did, one little bug flew out, smiled, and flew away. That little bug was named HOPE. And that little bug made all the difference as it offered the encouragement required by the community to believe that they could make the world a better place to live, in spite of the bad stuff. And by the way, Zeus’ heart was softened, and he freed the other brother.

What’s the moral of the story? Put simply, hope is what gives us the courage to act and to live in a world of threat. Hope is what allows us to overcome our fear.

Right now, there is no cure for FTD. However, I am hopeful that someday there will be. I’m also hopeful that those of us living with dementia can improve the quality of our lives by being honest, transparent, and willing to make some changes in the way we live. I’m hopeful that by acknowledging but not giving into its challenges, we can make dementia a stop along the way of our human journey, and not the end of the script.

Friends, we are living in uncertain and trying times. The powers and principalities of this world are again at odds with the grace and wisdom of God. Yes, many are losing hope. It is our sacred task and honor to present our hope to the world. For without hope, all is lost.

As St. Paul writes, “May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that you may abound in hope.”

And, as our cat Samson delightfully reminds us, boxes are meant to be opened and fully enjoyed.